By Jason Sheehan

CERES Outreach Educator

Sustainability carries across every resource we use as a species. In Australia, water is one of the vital resources we can all aim to use sustainably. But what does being sustainable mean? Well, when we think of a resource like water, being sustainable means maintaining our use of water at a certain rate or level. Obviously we can’t afford to run out of water.

There are a number of reasons why water is so precious. We will look at water globally, learn about where it comes from, how we store it, which will include the reasons for water restrictions at certain times of the year around our country. And most importantly we will look at our own water consumption.

The title of this article is ‘Water, water, everywhere…” which refers to ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798. This poem recounts the experiences of a sailor who has returned from a long sea voyage, and while its author shares no particular standpoint or opinion on sustainability – indeed the concept of sustainability in its current form would not have widely discussed by Coleridge in the late eighteenth century – it is the few lines this poem is most notable for that are of interest:

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

Such words are quite relevant under the umbrella of sustainability. Particularly when we consider the encroaching sea due to the climate crisis and the availability of drinking water in our world. More than two thirds of our planet is covered in water. Of that, about 97% is found in the oceans. We cannot readily source our water needs from saltwater. Even desalination has its hurdles. So the remaining 3% is fresh water, but most of this is unavailable, locked up in glaciers, polar ice caps, in the atmosphere and soil. Much of this is polluted or is found too deep beneath ground level to be collected affordably. This leaves only 0.5% of earth’s water as fresh, accessible drinking water.

Access to fresh water is limited in many locations around the world. In developed areas, generally water is piped from dams to our homes. But in rural areas, island nations, deserts and mountainous lands, people often rely on tanks or other methods to store water, which means they are often at the mercy of the skies. They need to capture and store rain when the opportunity comes, and with a dry climate this is particularly problematic. Even our dams which collect water from quite large catchments can still often fall to low levels. As populations in metropolitan areas increase, so too does the intensity of water use. When this happens water restrictions are often enforced meaning that our water needs to become limited. At certain times these restrictions can be quite severe too. As a population, as a country, we cannot afford to run out. Unfortunately, location is the key to this enigma.

The ways in which the climate functions across the oceans, along with the geography of this land on which we make our homes, means that some areas remain intensively dry while others are victim to flooding events and humidity. This is true all around the world, and as a species we have grown with technology enabling the reliability of available water. But say for instance the water ran out at just your home. Consider not being able to get any water all day, or for a week. Now exacerbate this problem across your neighbourhood, your suburb, your city, your state.

The human body is about 60% water. We need on average about three litres of water per day to maintain good health. Maybe you are lucky in not often needing to drink water itself, but we still get water from our food and other beverages. Three litres of water can seem a daunting target if we tried to just consume that quantity each day. In hotter environments many of us would certainly get close though. But conversely, the rate at which the human body loses water depends on its environment and its activity as well. This does not make for a simple science.

Now with this information I have a thought experiment for you.

Imagine an olympic sized swimming pool, vast and glorious. How long would it take for a single human being to consume the entire volume of that pool if it were freshwater?

Consider three litres a day. An olympic swimming pool hold about 2,500,000 litres of water. So this works out at 833,333.3 days, or about 2283 years. An impossible feat for a person at the top end of a human lifespan.

But, what if I were to give you another answer? What if I told you it was possible to consume this same volume of 2,500,000 litres of water in just 388 days? That’s just over a year. One person. Three litres a day! I’ll explain.

I want to introduce you to, or perhaps remind you of, something called invisible water, or virtual water. These terms are synonymous. Yes water is mostly colourless. Invisibility itself is not what we will be discussing. Instead, let’s think of the water used to grow the things we eat and the clothes we wear, the products we buy. Everything needs water.

The major use of fresh water on our planet is for agriculture. About 70% of fresh water use by humans goes to this sector. This makes complete sense when plants need water to grow, and we grow everything we eat other than salt. It can be pretty startling though when we examine the figures of irrigation and drinking water for livestock.

A cup of tea will use about thirty litres of water by the time we drink it. A lot of this is in growing the tea plant. Then there is processing, packaging, and finally what boils in the kettle. Comparatively, a cup of coffee uses around 140 litres to produce the coffee itself. The addition of milk can add another 153 litres of water to produce just 150mL of dairy milk. That makes 293 litres of invisible of water for that morning caffeine hit.

A disclaimer is necessary here though. These values represent empirical data from specific case studies. The average invisible water use of any product will be relative to where it is grown as the climate will impact upon its water needs. While the actual water consumption of a kilogram of any produce discussed here may be more or less than the values presented, it still tells a story. A lot of water goes into the food we take for granted.

A pistachio will need 2.8 litres of invisible water.

A single almond needs over 4 litres.

A walnut, 18.5 litres.

A tomato uses 12.5 litres.

And a single orange will use 52 litres of invisible water.

This gets even more interesting.

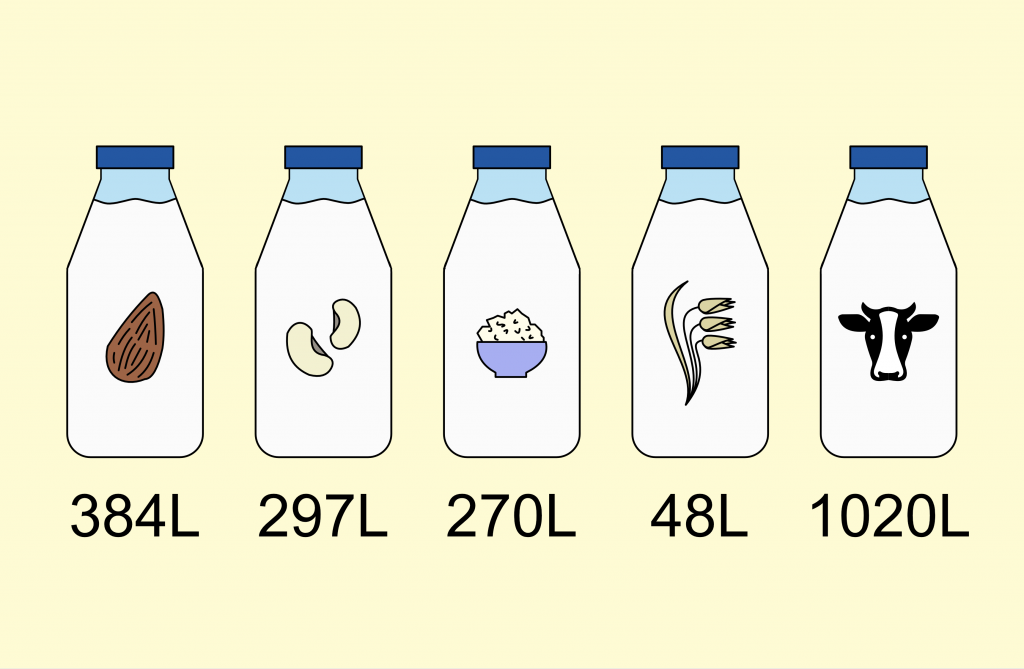

Let’s return to milk and consider our choices. For a litre of almond milk you’ll consume 384 litres of invisible water.

A litre of Soy milk will use 297 litres of water.

A litre of Rice milk is 270 litres of water used.

Oat milk per litre comes in at about 48 litres of invisible water.

Compare all this to the dairy milk we used before and 1 litre of cow’s milk will earns you 1020 litres of invisible water.

The water consumption of agriculture is a concerning topic. Not only to the consumer but the farmer as well. What is and isn’t profitable, or financially sustainable, makes other choices even more difficult. To be conscious of our own consumer choices, and our efforts towards sustainability, it is important to consider this crucial factor. Buying and eating local is certainly best practice, but water should be acknowledged.

If we were to put together a bit of a rough calculation on what food we would eat in a day, the numbers stack up quickly. By adding a few bits of chocolate into the mix at 17,196 litres of water per kilogram (kg), our water consumption outside of the plastic free, eco friendly bottle becomes difficult to fathom.

One estimate comes in at 6435 litres of invisible water consumed by an individual in a single day. This will very person to person of course, and if we go vegetarian the figures might look better. Beef can come in at 15,500 litres of water per kg when we also consider the pasture and grain consumed by cattle. Lentils arrive at 5863 litres per kg. Tofu lands at 2140 litres per kg. Its important to remember that whatever food choices we make we need to maintain a healthy diet either way. but if we get back to the swimming pool we can start doing the math.

If we consumed this estimated value of 6435 litres of invisible water a day, and let’s not forget the 3L we are supposed to drink, then as an individual we can get through the volume of that olympic pool in just 388 days. That is quite remarkable. Think of every human being doing that around the world, even where the diets and food availability changes. So I ask you then, is this sustainable? Or perhaps more importantly, what does sustainability look like when we consider invisible water?

If we consider our food choices alongside the water we use at home and the materials we clothe ourselves with, we can dramatically reduce our impact. It’s certainly a collective effort though. I encourage you to think about this. Think about the foods you eat. Research the water used and make an informed decision. You don’t have to give things up, but understanding your water use is a big part of trying to be sustainable. In a world facing increasing problems, water will continue as the source of life.

We often see this image or hear talk of our carbon footprint. But we have two feet, and our water footprint is just as important. Think about yours and see what you come up with.

So let’s return to that poem one more time.

Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink. When we realise how little water there really is available to us in our watery world, this line of the poem could not be more fitting. As the human population increases and the climate crisis drives more severe weather, the goal of being sustainable with our water use seems more and more difficult. The goal posts are constantly shifting. We must shift with them.

Sources:

Water Footprint Network: Using the water footprint concept to promote sustainable, fair, and efficient fresh water use – https://www.europenowjournal.org/2018/09/04/water-footprint-network-using-the-water-footprint-concept-to-promote-sustainable-fair-and-efficient-fresh-water-use/

Live vegan, save how much water?! – https://www.veganaustralia.org.au/water

The Reason Why You’re Using MUCH More Water Than You Think – https://ahbelab.com/2015/07/23/the-reason-why-youre-using-much-more-water-than-you-think/

Sustainable or not? A look at non-dairy milk alternatives – https://www.1millionwomen.com.au/blog/are-non-dairy-milk-alternatives-sustainable/